The second of a three part series analysing the British Association of CFS/ME (BACME) guidelines on severe ME. I have chosen to write extensively on this subject, as the guidelines encompass several themes that are important to me.

In Part 1, I highlighted some positive aspects of the BACME guidelines, as well as giving an overview of my concerns.

Here, in Part 2, I look more closely at the guidelines’ focus on deconditioning and graded exercise therapy (GET), as well as their failure to address issues of critical importance in severe ME.

As this is a lengthy piece and will likely be a challenge for those who are ill, I have once again included a short summary at the end of each section, for anyone unable to read the full text.

Part 2 contains the following:

- The guidelines’ underlying message

- Pressure on families

- When progress isn’t possible

The guidelines’ underlying message

The BACME guidelines assume that deconditioning is a major factor in the continuation of symptoms in severe ME. This is not explicitly stated, but the implication is woven throughout in continual references to the need for rehabilitation, goal setting and gradually increasing activity. A subsection identifies the “Overall Treatment Approach” as “Incremental pacing and grading up activities” and goes on to say:

“Most specialist services […] will incorporate incremental pacing and grading of activities to aid rehabilitation.” (BACME Working Group on Severe ME , Version 2, page 14)

Such an approach will not come as a surprise to anyone who has suffered from ME during the last 30 years. The biopsychosocial (BPS) model of the illness holds that while there may be an initial viral or other physical trigger for ME, ongoing symptoms are the result of the patient avoiding activity and becoming stuck in a state of anxiety at attempting anything new. BPS proponents claim that recovery can be achieved through a structured programme of increasing activity (graded exercise therapy, or GET) and a specially tailored form of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) to challenge the patient’s “belief” that they are ill. Despite decades of extensive research evidence showing active disease processes in ME, the BPS school of thinking has held sway among the medical profession since the 1980s.

Perhaps what has changed is the way in which these views are presented. Open hostility towards patients and overt references to GET have been removed, at least from publications such as this. (In clinical practice, they remain sadly prevalent.) We now have sympathetic acceptance of symptoms, but still with the same underlying belief: namely that patients can recover, or at least substantially improve, if they repeatedly stretch their boundaries and increase activity.

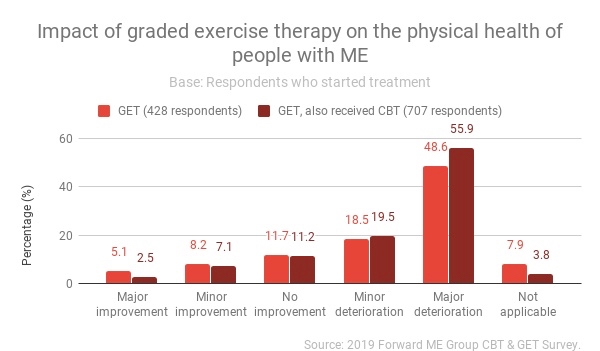

Graph courtesy of #ME Action UK

In reality, such an approach is known to cause a worsening of symptoms. A hallmark feature of ME is post-exertional malaise (PEM), described by Prof Ron Davis of Stanford University in this way: “Patients often get worse, sometimes irreversibly, when they exert physical, emotional or cognitive effort over their own personal limit.” Research has shown an abnormal physiological response to exercise that appears to be unique to the illness. In March 2019, a meta-analysis of 20 years of studies found “overwhelming evidence” of an abnormal heart rate response to exertion in ME patients, of a type not found in any other illness, nor in deconditioning.

Although the 2011 PACE trial suggested that GET and CBT were beneficial in ME, reanalysis of the data showed that neither had any significant benefit. An analysis of patient surveys, published in the Journal of Health Psychology in 2017, concluded that “GET fails to help the majority of ME/CFS patients improve symptoms and has a marked negative impact on approximately 50% of patients.” A large survey earlier this year, conducted by the Forward ME group, concluded that “graded exercise therapy (GET) is harming a large majority of people with ME receiving this treatment in the UK”, with “more than 3 times as many people reporting severe illness after GET than before”. In January 2019, MPs in the UK unanimously passed a motion calling for the suspension of GET and CBT, in recognition of the harm caused by these treatments.

In 2019, MPs called for GET to be withdrawn

And yet the BACME guidelines state:

“It is important to work with the person to establish a pattern that they feel they can sustain or can do for a few repetitions in the day. This should be trialed and adjustments made to make sure it is a stable baseline. Then individual components can be increased gently, so it may initially be by seconds. Each level is usually sustained for a few days before increasing again.” (Ibid, page 14)

There is no warning given that any increase at all is dangerous for many with severe ME, or that even reaching a stable baseline might be impossible in the most critically ill. There is certainly no suggestion that attempting to increase activity every few days would be wildly optimistic even for a milder case of ME, never mind someone severely affected. Nor is there any mention of the fact that PEM can be delayed by days, meaning that potential damage is impossible to assess in so short a period of time. That such a statement could be made shows a dangerous lack of understanding of just how delicately it is necessary to tread.

In their favour, the guidelines do stress the need for any treatment programme to be tailored to the individual, and acknowledge that “there is no clear evidence for treatment of CFS/ME patients who are severely affected.” But the encouragement given to professionals to proceed at the patient’s own pace is undermined by the expectation that activity will be steadily increased at some point.

“The goal is to enable individuals to find ways to better balance their activity and quality rest within their immediate limitations to establish more predictable and maintainable patterns of activity. This in due course can be followed by a slow stepwise upward grading to achieve sustainable a [sic] meaningful change.” (Ibid, page 14)

In summary:

The guidelines assume that deconditioning is a major factor in the continuation of severe symptoms.

There is repeated reference to the need for rehabilitation, goal setting and gradually increasing activity.

The guidelines do not warn of the risks of graded exercise therapy (GET), which have been demonstrated in medical research and through patient surveys.

Professionals are encouraged to proceed at the patient’s own pace, but this is undermined by the expectation that activity will be steady increased at some point.

Pressure on families

The guidelines also place pressure on family members, and effectively attribute blame for the continuation of certain symptoms. In a case study on sound sensitivity, for example, the guidelines say, of patient ‘Ms D’:

“Intolerance to noise was a big problem so family members tried to be very quiet around the house to prevent Ms D withdrawing to her bedroom. Initially this approach was useful when Ms D was very unwell but it had the effect of increasing her sensitivity to sound over time.” (Ibid, page 16)

There could be many reasons why Ms D’s sound sensitivity worsened, and it is worrying that the only one considered is her family’s accommodation of her symptoms. When household noise can have the most terrible consequences for those with severe ME, families should be encouraged to be as quiet as possible for as long as is needed – not told that they might be making the situation worse by doing so.

Sensory sensitivities in severe ME

The guidelines could have taken this opportunity to share valuable advice on coping with sound sensitivity in a family context, as the conflicting needs of someone with severe ME and other household members – particularly if they include children and young people – can be a struggle for all concerned. In most cases the problem is not that the person with ME is too sheltered from noise, but that the sound of other household members going through the basic motions of daily life (which simply cannot be avoided) is too much to cope with and causes an ongoing strain on the body.

If there is improvement in the person with ME, it might then be possible to gradually increase the level of household noise. (In my experience, this was something that happened naturally as my sensitivities eased.) But it is wrong to suggest that this crippling symptom – or indeed any other – can be treated by modifying the behaviour of either of the person with ME or their family.

In summary:

The guidelines provide a case study on the subject of sound sensitivity.

It is suggested that ‘Ms D’ experienced a worsening of her sound sensitivity because her family were too quiet around the house.

There are many reasons why Ms D’s sound sensitivity could have worsened, yet no other explanation is considered.

Household noise can have terrible consequences for the most severely ill.

The problem is usually not that a shared house is too quiet, but that the unavoidable sounds made by other household members are a constant strain on the person with ME.

Families should be encouraged to be as quiet as possible for as long as is necessary.

It is wrong to suggest that this crippling symptom – or indeed any other – can be treated by modifying the behaviour of either the person with ME or their family.

When progress isn’t possible

What happens in cases where no progress is possible? The 2002 Independent Working Group Report to the Chief Medical Officer stated that:

“Progressive deterioration can occur in some patients with CFS/ME; the existence of such patients, many of whom are among the more severely affected, must be recognised. Many need special attention in the delivery of care and the provision of support.” (Independent Working Group Report to Chief Medical Officer, 2002)

Such a scenario is not even addressed in the BACME guidelines. Instead they say:

“Progress will have small or large setbacks on the way, but it doesn’t mean things won’t move forward over time with patience and perseverance.” (BACME Working Group on Severe ME, Version 2, page 15)

At face value there is some truth in this: setbacks do not necessarily mean that progress in the future will not be possible. But the emphasis on perseverance is concerning, as is the assumption – yet again – that improvement is a given if only the patient complies with the treatment programme. There is no recognition of patients whose condition progressively deteriorates, or even those who plateau and cannot make progress.

Sophia Mirza died after being sectioned

“It is possible to do things, despite the person feeling unwell, with careful planning and timing.” (Ibid, page 15)

Statements like this represent a terrible lack of understanding ME at any level of severity. Careful planning and timing do indeed form an essential part of survival for those severely affected, but they do not mean that anything is possible. This again comes from the erroneous assumption that the person with severe ME can do more, if only they apply themselves correctly.

The picture painted by the guidelines is problematic on numerous levels. A professional approach that begins with apparent understanding can easily turn into something forceful when the progress expected is not made. I have worked with many professionals who, when I wasn’t getting better – or not progressing at a rate they deemed appropriate – decided that the only possible explanation was that I lacked motivation and wished to remain ill. This despite me driving myself to collapse trying to meet their demands.

The BACME guidelines constantly reinforce the idea that the person with ME can and will improve if they comply with a graded exercise programme. This has concerning implications for those who do not make progress, or even deteriorate. It is not uncommon for adults with ME to face enforced psychiatric care when doctors decide that their ongoing illness cannot have a physiological explanation. (High profile examples include Sophia Mirza, who later died, and Karina Hansen.) Similarly, children with ME can be placed under threat of child protection proceedings when their parents are deemed responsible for their lack of progress.

In such a climate, the reality that ME can be a life-long, intractable illness needs to be made very clear. The BACME guidelines completely fail to do this.

In summary:

The 2002 Independent Working Group Report to the Chief Medical officer recognised that some people with ME progressively deteriorate.

The report stated that these cases must be recognised and given special attention.

The BACME guidelines do not acknowledge that progressive deterioration can occur.

Instead they suggest that progress will happen at some point if there is “perseverance”.

This has serious implications for those who cannot improve.

Adults with ME can face enforced psychiatric care when doctors equate lack of progress with psychological disturbance. Similarly, children with ME can be placed under threat of child protection proceedings.

The BACME guidelines fail to make clear that ME can be a life-long, intractable illness.

This is the end of Part 2 of my analysis of the BACME guidelines. In the final part I ask whether deconditioning is relevant in the management of severe ME, and, if so, how it should be addressed. I also offer suggestions of ways in which the guidelines could be improved.

Images: Iceberg by Annie Spratt on Unsplash; Big Ben by Jamie Street on Unsplash; Sophia Mirza, courtesy of sophiaandme.org.uk